* See T/N at the end

That night, Rajiva stays in the temple and does not return [home], so Pusysdeva brings Xiao Xuan over to keep me company. In the afternoon of the next day, Pusysdeva comes and tells me that Rajiva had the monks chanting mantras all night. Lu Zuan had woken up in time but was a little scared to see Rajiva. Lu Guang lost face greatly and did not want to stay in Subashi City any longer, so he ordered that they leave for the capital early next morning. Pusysdeva and his wife have been missing their children so they will also return home with Bai Chen tomorrow.

The couple sits with me until Rajiva return from the temple and reluctantly says goodbye to us after dinner. Before they leave, Pusysdeva tells us to rest assured for after this incident, Lu Guang should learn that he can exhaust all methods but will not able to defeat Rajiva. Even though he is prone to slander without thought, Lu Guang is still a man [of his word]. Since he announced his agreement [to the terms] in front of so many people, he ought to keep his promise and stop tormenting us.

Rajiva and I both sigh in relief. Things will finally calm down. Lu Guang will not leave Kucha until March of 385 CE, which is next year. At that time, he will bring Rajiva along but at the very least, we will have a peaceful life for four months. I tell Rajiva this during the night. He holds me in his arms and is silent for a while before he speaks:

“Going to the Central Plains was originally Rajiva’s mission, [so] I will not evade it. But, will you accompany me?”

“I will accompany you until death,” I look up into the pure eyes that have captivated me since he was thirteen and tell him in my surest voice, “I will protect you, stand behind you, [and] assist you in completing your mission.”

A brilliant smile lights up his being; he glows like a deity. But he seems to suddenly remember something, for his smile fades and he looks at me sternly:

“Ai Qing, do not talk to anyone else besides Rajiva about your true identity, and do not tell anyone their future. Also, do not use your abilities from the future unless you absolutely have to.”

He gazes out at the windows. His mind seems to be full of erratic thoughts. He looks like there is a cloud hovering over him, making his brows furrowed.

“[I am] afraid that, you being able to foresee the future, in these turbulent times, would be of more interest to those who ambitious and ruthless in character than your identity as a celestial being…”

My heart shudders. The way he speaks resembles that of my ‘boss’1. But ‘boss’ said this to me because he did not want me to alter history, whereas he [Rajiva] is only worried about my safety. Before, I did not care about this because I thought of myself as a tourist and that if anything major happens, I can just go back to the modern times. But if you really want to survive in this miserable era of chaos, the instant you are inattentive, it can possibly result in ‘misfortune from the mouth’2. Now that I am no longer by myself, I cannot run away—I cannot hurt him.

1 ‘Boss’ here refers to the nickname Ai Qing has for her history professor, who is the advisor to the time travel project.

2 祸从口出 huòcóngkǒuchū – a chengyu (Chinese four-character idioms—I’ve been referring to them as simply ‘Chinese idiom’ in my previous T/N but that was too broad of a term. 成語 or chéngyǔ, lit. ‘[already] formed words’, is the correct term). This chengyu, as you can probably tell from the words, means that a loose tongue can cause trouble.

I give him a [modern] military salute and solemnly swear:

“Worry not, I will only focus on the role of being your wife; absolutely only have ‘eye looking at nose, nose looking at heart;’1 ‘cautious in words, careful in behaviour;’2 low-profile in conduct; and never disclosing my secrets.”

1 眼观鼻,鼻观心 (yǎn guān bí, bí guān xīn) – the above is a literal translation; this is a Chinese expression that has two meanings (per baike baidu): 1) to indicate bowing one’s head out of shyness/embarrassment, and 2) having a focused mind, heart not distracted. The second meaning applies in this context.

2 谨言慎行 (dīdiào zuòrén) – a chengyu that came from《礼记 · 缁衣》or Lǐjì – Zī Yī (Book of Rites – “Black Robes”), which is a classical text in Confucian canon.

He laughs, dazzling the room with his elegant and handsome face. It has been a long while since I have seen him laugh so freely that for a moment, illicit [desires] arise and like a smitten fool, I stare at him open-mouthed.

He brushes my nose and asks softly, “Only a wife?”

“Huh?” I swallow my saliva* and stare at him, puzzled.

[T/N: Basically, she was drooling over his handsomeness after seeing him laugh earlier]

A familiar blush takes over his face. He embraces me from behind, head resting on my shoulder, slender palms gently covering my flat stomach.

“Could it be that…” he pauses, breath a bit heavy, voice a tiny whisper right into my ear, “you do not want to be a mother?”

I freeze. Mother? Child? Children of him and me?

I turn around and see that his clean, relaxed face is blushing, yet he is also looking at me with a fixed gaze, a shy and expectant smile on his lips.

“You…” Somewhat unsure, I whisper and ask, “You want to have children?”

“Rajiva has never dared to think that there will be a child sharing his blood in the world.” His face has been blushing this whole while, but his eyes are firm, “After living together with you, however, [I] really want to have a child. If possible, give birth to a girl who looks like you. Rajiva will definitely love the child with all of his heart.”

My nose stings: “Are you not afraid of denouncement from people?”

“Breaking precepts, taking a wife, which one to denounce? You know [me], the comments by this generation or later generations, Rajiva does not care at all.” His face looks calm, but there is still a note of melancholy when he pauses in thought, “I just want to have a child of ours, [so that] in the future, if you have to go back, allow me to keep the child-”

“I will not leave!” I cover his mouth and speak fiercely, “Do not forget, we have tied our hems to promise a hundred years.* You want to get rid of me? In your dreams!”

* [See Ch.55, specifically my T/N for the chapter’s title]

His eyes burn in response, brows finally loosening, and then a light peck is placed on the palm of my hand that is covering his mouth. Something numb travels down my spine, my whole body shudders slightly. He picks me up—he likes to carry me to the bed these days. Ear and temple rubbing against each other1, fluttering and lingering, yet at the moment when the climax is reached, he suddenly withdraws. He has never acted like this before, so I cannot help but ask, breathless: “What’s the matter?”

1 耳鬓厮磨 (ěr bìn sī mó) – lit. ‘ear [and] hair on temple rubbing against [each other]’, this is a chengyu that is also a euphemism for intimate relations [or per MDBG: “a very close relationship”, snort], which originated from 紅樓夢 (Hónglóumèng) or Dream of the Red Chamber, one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels. [It does not surprise me that a euphemistic idiom was derived from this novel. But also, fun fact: ‘Redology’ is a term used to describe the field of study exclusively devoted to this novel!]

He is still breathing heavily, takes a moment to rest, then brushes aside my sweaty hair and softly says:

“At present, it is not yet the time to be carrying a child. We will be departing in the third month of next year, and it would take half a year to arrive at Guzang.* There will be many bumps on the road, if you are pregnant, how will you be able to endure?” He reaches out and pulls me into his arms, and then kisses me on the forehead, “Once we arrive at Guzang and everything settles down, our household can have one more addition.”

* Guzang (presently part of Wenwu, Gansu) was the capital of Former Liang (320–376 CE), Later Liang (386-403 CE) – the state established by Lu Guang, and Northern Liang (397-439) – established by Duan Ye.

Map of China during the Sixteen Kingdoms Period as of 391 AD

I bury my head in his arms and listen to his powerful heartbeat. I smile shyly but deep in my heart, I am full of worries. We have never tried to prevent pregnancy, but what he said today has reminded me. Half a year on the road, over a long distance and using transportation in the ancient times, will definitely not be as comfortable as travelling in the modern times. Under such circumstances, I really should not get pregnant before we reach Guzang. But what I worry about the most is not this but: Can I even get pregnant? This body has been in and out of the time-travel machine several times. I do not know whether irradiation has damaged my fertility or not. And even if I can get pregnant, will I be able to give birth smoothly? I am not afraid of the primitive delivery techniques of ancient times, but I cannot sustain any injuries.* Would giving birth be counted as an injury?

* [T/N: As a refresher – during her last time travel, Ai Qing has learned that irradiation has caused her body to heal at a much slower rate, which was why the wound on her arm never healed properly, almost resulting in necrosis, so she had to return to her era to get surgery. See Ch. 34.]

I have tried to tell him many times, but looking at the way the corners of his mouth are curving and how he eager he is about the future, I end up holding back. If he learns of the true price I paid for my journey, how much worry and guilt would it bring to him? Our happiness is so hard-won—I cannot destroy it.

I glance outside. My backpack is currently lying in some storage room, with my time-travelling watch and anti-radiation jacket stored inside. There were many times where I wanted to throw away this source of radiation,* but I kept thinking about boss’ words. Hesitant and indecisive, in the end, I was unable to sever the ties with the 21st century. I could only store the bag far away from my sight and hope that I would never have to use them again.

[T/N: The items she brought from her era, like her, have also been contaminated with radiation during the time-jump. This was why she never brought along any perishables.]

“What are you thinking about, looking so silly?”

He is lying on his side, looking at me, his hand playing with my hair, eyes overflowing with affection.

“There is another way to prevent carriage.”

I regain my spirits and explain to him the concept of ovulation and safe period [in menstruation cycle]. He listens carefully and asks me in detail about my modern physiology knowledge, frequently exclaiming in admiration of the wisdom gained after a thousand years. I cannot help laughing inside. He really has come to accept that his wife is a person from the future.

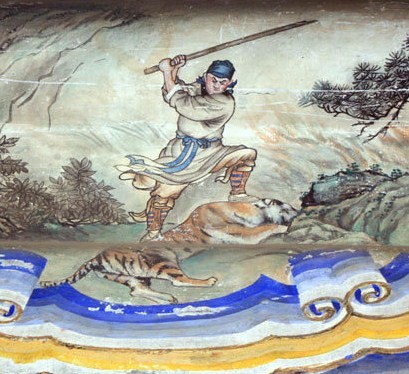

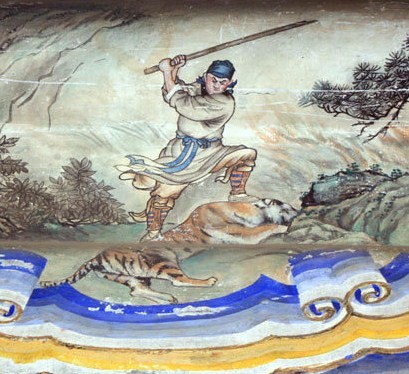

An illustration of Wu Song at the Long Corridor in the Summer Palace, Beijing

The happy little days momentarily make us forget about our worries. My cooking skills have improved a lot, so he often brings the lunchboxes I made for him to the temple. After learning how to cook in ancient times, I also begin to learn how to wash clothes the ancient way. No washing machine, no detergent, no fabric softener, just balls of [Chinese] honey locust1, a washing board, and a wooden staff. The first time I followed Elder Sister Adoly to wash clothes at the Tongchang River, because I did not know how to use the staff, I almost broke into the posture of Wu Song beating a tiger2, causing laughter from the other women by the river.

1 Scientific name: Gleditsia sinensis, known in Chinese as 皂角 (zàojiǎo) [not to be confused with the North American-native plant], the seeds of the plant were turned into powder and kneaded into a ball, which produces bubbles when used so was highly effective for washing clothes. ‘Soap’ in Chinese is 肥皂 (féizào), which as you can see, derives from the name of the plant.

2 Wu Song is a character in Water Margin, one of the Four Great Classical Novels in Chinese literature, who often fights with a staff as his weapon. There is a story about Wu Song defeating a tiger in the novel.

Choy Sum

On my way home after washing clothes, the people I meet on the streets all avoid me. I tell myself that it is okay, that I do not need to mind what others think of me. I stand tall, hold my head high, and keep walking. But all of sudden, a woman steps forward to stop my tracks, scaring me. She gives me a handful of choy sum* and says hesitatingly:

* The text says 菜心 (càixīn), which is a transliteration of the Cantonese name.

“Princess, this was just picked. The master made a prayer of blessings to treat my child, and it was the master’s Bodhisattva-heart that saved him. My family is poor, we got nothing else, so I hope Princess will not mind. May Princess and the master be blessed with peace and luck!”

In a daze, I take the choy sum, which still has drops of water dripping from its young green leaves. This is the first time I have received blessings from a stranger. Aside from thanking her, I am not able to say anything else. When I arrive home, I keep staring at the choy sum until Rajiva returns. I excitedly tell him the origin of the vegetable. He merely smiles, lost in thought.

The next day, he unexpectedly returns home earlier than usual. I am learning how to make naan in the kitchen. He asks me to wash off the flour on my hands and face and go change, but does not say what for. After I have finished changing per his inexplicable request, he takes my hand and walks out onto the streets.

My heart is shocked. I have never walked with him so openly, let alone while holding hands! I want to withdraw my hand, but he only holds it tighter. He smiles at me, a smile like a spring breeze, filling my heart with a breath of warmth. I hold myself tall and smile back at him. Together, we walk on the streets of Subashi City.

Anyone who sees us is unable to hide their surprise. Rajiva greets people as always, humble and respectful, but his bearing is exceptional. Having been the abbot of the Cakuri Temple for so many years, he has come to know all of the residents of Subashi. He brings me to every door, chatting with people as if we are an ordinary couple on an evening stroll after dinner. The initial awkwardness eventually eases into acceptance as more and more people begin to talk to us, some calling me “Princess”. There are also many monks on the streets. They look at me in surprise when they pass by, but still clasp their hands to greet Rajiva. He returns their greeting as usual, but also insists on them calling me ‘master’s wife’1. It is dark by the time we get back. My hands and his are full of things—all kinds of vegetables, fruits, and daily necessities. They were given to us by the people, and it was useless to even try to refuse.

1 师母 (shīmǔ): a respectful term for your 师父 or shīfu (master/teacher)’s wife.

From then on, every time I leave the house, I no longer receive looks of suspicion. Every day, there is always someone who comes to visit me, gives me things, and talks to me. Even though I am not used to being an object of curiosity, being accepted by the public makes me quite happy.

Rajiva is reading by the oil lamp, while I sit beside with my basket of threads and needle. I place a sheet of sketching paper on the ground, tell him to take off his shoes and step on it, then I use a pencil to sketch the outline of his feet. The past few days, Elder Sister Adoly has been teaching me how to make cloth shoes and how to fill the soles. My sketching paper has found a new use. In the sewing basket is a garment of his that has a hole on the elbow, which he refused to get rid of. After tracing the outline for the shoes, I sit quietly beside him, cut a piece of cloth of the same colour, and patch up his shirt.

“Ss!”

Sure enough, he drops his book and checks my finger. Then, as I expected, he puts my finger in his mouth and sucks. Haha, I have looked forward to this warm scene!

“Why do you need to do this work?” He raises his eyes and upon seeing me giggling, looks a little angry, “Why not let Elder Sister do it?”

I raise my eyebrows at him, full of mischief, not wanting to explain to him that I wanted to experience this. There is a scene that often appears in historical dramas: the scholar husband is reading; his gentle wife is sitting beside, doing needlework. Then the wife pricks her finger with the needle, and the husband sucks on her finger, full of heartache. The men and women of the 21st century are always busy. Even if a married couple is at home at the same time, one is watching soccer and the other is surfing the Internet. It is hard to find the warm scene of “trimming candle’s wick together by the west window”.*

* This is a reference to a line in the poem《夜雨寄北》by Li Shangyin:

《夜雨寄北》

君問歸期未有期

巴山夜雨漲秋池

何當共剪西窗燭

卻說巴山夜雨時

“Written during the rain one night and sent back north”

You asked when I was coming back

no date fixed yet;

in Ba’s hills the rain by night

spills over autumn ponds.

When will we trim candle’s wick

together beside west window

and speak back about this moment

of night rain in hills of Ba?

– Stephen Owen, Anthology of Chinese Literature (Beginnings to 1911), p. 515

Such a state of mind, I do not know how to explain to him, so I can only flash him my silly grin and try to change the topic:

“What book are you reading?”

My casual question somehow makes him blush. Curious, I pick up his book. Rajiva studies a wide range of areas, reads almost every kind of book, and is also a fast reader with a superb memory. What he was reading is a medical text in Han. I know he sometimes studies medicine and occasionally treats people, but why the blush? Suspicious, I open to the page he was reading. The word ‘gui shui’* jumps into my eyes. My cheeks redden.

* 癸水 (guǐ shuǐ): ancient Chinese term for menstruation. 癸 = the 10th Heavenly Stem (Heavenly Stems were names of the days of week), and 水 = water. The ten Heavenly Stems also correspond to 五行 ( wǔxíng) the Five Elements—each element contains two Heavenly Stems, further broken down into yin and yang. 癸 corresponds to the yin of the Water element.

When we were under the house arrest, he once saw me leaning forward, clutching my abdomen in pain. Frightened, he quickly checked my pulse for a diagnosis. I had blushed and explained to him about menstrual cramps, and how they would make me suffer for hours on the first day [of my period]. He was so flustered that he did not know what to do with his hands and kept asking me, “Does it still hurt?”

The second time he witnessed it was after we got married. Having gained some experience, he was extremely gentle with me during those days and tried to help by rubbing my stomach. I did not expect him to now read a book on how to treat menstrual cramps. A current of warmth travels through me. Looking at his flushing face, I cannot help but laugh.

“You will feel pain in three days.” Seeing me laugh, he looks a bit annoyed. “Tomorrow, I will ask Kaodura to get medicine. You must try to drink it, for it will help.”

I freeze for moment.

“How do you know the time [when it will happen]?”

“I am your husband, naturally I ought to know,” he gently knocks on my forehead, his face still red, “Only you, scatterbrained* lady, would not even remember this.”

*傻头傻脑 (shǎtóu shǎnǎo), a chengyu that originated from Hongloumeng. 傻 = foolish / silly, 头 = head, and 脑 = brain.

I stick out my tongue. To be honest, I never keep track of my menstruation cycle. Because a menstruation cycle is 28 days,* which is different from the number of days in the Gregorian calendar month, so I always get confused. Whenever I feel like my period is approaching, I would bring along sanitary pads. In preparation for this time jump, I had stuffed two years’ worth in my backpack, taking up quite a big amount of space.

* [T/N: Just want to correct that it is 28 days on average, but this is not universal for all people. To be more accurate, the range is 21-31 days.]

I wrap my arms around his waist and lean against his shoulder, acting spoiled1:

“Your memory is better than mine, so you remember it for me!”

1 撒娇 (sājiāo) [T/N: According to Chinese people, this is one of the most difficult words to translate as there’s no single English word that can encompass every aspect of it. It was once a gendered term/act (women’s) but is now gender-neutral. Depending on context, it can be translated as: cajole / pout / sulk / wheedle / coquettish / flirt / etc. One can use it as a child, as an adult, and the receiving end can be a family member, a friend, or a lover. It is acting cute with a dash of brattiness, but short of being annoying. To be able to sajiao at someone indicates an easy familiarity and that you feel confident of their love for you. There is an equivalent word in Vietnamese, which is “làm nũng” or “nũng nịu”, so I can empathize with the Chinese on the difficulty of translating this word.]

“You…”

I tighten my arms around his waist and bury my head into his chest, breathing in his scent: “One who is loved is qualified to be lazy.”

He laughs and pulls me onto his lap. I hook my arms around his neck, rest my head against his shoulder, and quietly read the book with him. He is my comfortable stool, forever a stool.

An old song comes to mind: “[I] once asked over and over, secretly in the dark / Only to know that a simple and leisurely life is the truth.”1 No matter how dazzling and beautiful a love is, it will eventually dull. But a dull life where one can moisten each other with spittle2, sharing warmth with him bit by bit3, already makes me feel as sweet as syrup4.

1 Lyrics from the song《再回首》”Looking Back” by Taiwanese singer Su Rui, released in 1988. [See T/N at the end of chapter for further notes on the lyrics as it contains a few chengyu.]

2 相濡以沫 (xiāngrúyǐmò), a chengyu: describes how two fishes would pass the water in their mouths between each other to survive; it means aiding each other in difficult times with whatever meagre strength you have.

3 点点滴滴 (diǎndiǎndīdī), a chengyu: lit. dot, dot, drip, drip.

4 甘之如饴 (gānzhīrúyí), a chengyu: means to willingly and gladly endure hardships together.

In this way, we enter the winter of 384 CE without any major winds and waves. His work turns fruitful: Most all the monks who fled before have returned, and everything in the temple has returned to normal. The suffering people endured during the war has made them more devout and faithful towards Buddha, which in turn makes him busy but happily so. And I have also mastered more survival skills of the ancient times—can cook, wash, sew, make shoes, and pickle. Every day, I follow Elder Sister Adoly to the market to buy food, and also foster a relationship with the neighbourhood ladies. Gradually, I begin to assimilate into the life of 1,650 years ago.

Of course, sooner or later, Lu Guang is going to call us to mind. That is why, after Kucha got its first snowfall, I see Di soldiers standing outside the gates. I smile bitterly. So the time has come early.

____________________________________________________________________________

Translator’s Notes:

RE: Chapter’s Title

Original text: 平平淡淡才是真

Pinyin: Píngpíngdàndàn cái shì zhēn

This chapter’s title refers to a popular Chinese saying but before we go there, we must first discuss the chengyu (yes, another chengyu) referenced within: 平平淡淡

平平 = average / plain

淡淡 = faint / dim / dull / insipid / unenthusiastic / indifferent

This is a chengyu that originates from 圍城 or Fortress Besieged (1947) by Qian Zhongshu, a satirical novel about middle-class Chinese society in the late 1930s (Source: Wiki). The chengyu is used to describe something that is average or below average, ordinary in quality, almost dull. Context of the phrase: The main character in Fortress Besieged was musing about his tepid feelings towards his fiancée:

“…假如再大十几岁,到了回光返照的年龄,也许又会爱得如傻如狂了,老头子恋爱听说像老房子着了火,烧起来没有救的。像现在平平淡淡,情感在心上不成为负担,这也是顶好的,至少是顶舒服的。快快行了结婚手续完事。” [Chapter 62 of Chinese text]

English: “If he were ten or fifteen years older and reached the moment of “twilight brightness,” maybe he could fall foolishly and madly in love. An old man’s love was said to be like an old house set ablaze. Once it started burning, there was no saving it. In the dull state he was in now, his emotions did not constitute a burden on his mind, which was just as well. At least it was quite comfortable. Better to get the marriage procedures over with as quickly as possible.” (Kelly, Jeanne, and Nathan K. Mao, translators. “Chapter 8.” Fortress Besieged, by Zhongshu Qian, New Directions, 2004, p. 293.) [In case you were wondering, yes, I got a copy from the library.]

Ironically, the chengyu is now part of a popular Chinese saying that claims such “dull state” is actually “truth” (真= ‘really / truly / true’), and that it is an ideal kind of life. This Chinese saying is our chapter’s title. From what I learned (ahem, through baike baidu and zhidao baidu; think Wiki and Quora), the meaning of the saying is not so much about living a simple life avoiding fame and fortune, but more about having a serene (or indifferent, depending on interpretation) heart as you go about life, about bearing the ups and downs in life calmly. With this second reference in mind, I decided to translate the chengyu as “simplicity”.

An alternate translation of this Chinese phrase (and in turn, this chapter’s title) that would capture the meaning better is “Simplicity makes life” (Huang Weijia and Sun Jiahui’s translation). I admit I like this translation better as there is a certain elegance to it, but I have already taken liberties with translating the chengyu so I decided to stick with a more literal translation for the rest of the phrase.

* See T/N at the end

That night, Rajiva stays in the temple and does not return [home], so Pusysdeva brings Xiao Xuan over to keep me company. In the afternoon of the next day, Pusysdeva comes and tells me that Rajiva had the monks chanting mantras all night. Lu Zuan had woken up in time but was a little scared to see Rajiva. Lu Guang lost face greatly and did not want to stay in Subashi City any longer, so he ordered that they leave for the capital early next morning. Pusysdeva and his wife have been missing their children so they will also return home with Bai Chen tomorrow.

The couple sits with me until Rajiva return from the temple and reluctantly says goodbye to us after dinner. Before they leave, Pusysdeva tells us to rest assured for after this incident, Lu Guang should learn that he can exhaust all methods but will not able to defeat Rajiva. Even though he is prone to slander without thought, Lu Guang is still a man [of his word]. Since he announced his agreement [to the terms] in front of so many people, he ought to keep his promise and stop tormenting us.

Rajiva and I both sigh in relief. Things will finally calm down. Lu Guang will not leave Kucha until March of 385 CE, which is next year. At that time, he will bring Rajiva along but at the very least, we will have a peaceful life for four months. I tell Rajiva this during the night. He holds me in his arms and is silent for a while before he speaks:

“Going to the Central Plains was originally Rajiva’s mission, [so] I will not evade it. But, will you accompany me?”

“I will accompany you until death,” I look up into the pure eyes that have captivated me since he was thirteen and tell him in my surest voice, “I will protect you, stand behind you, [and] assist you in completing your mission.”

A brilliant smile lights up his being; he glows like a deity. But he seems to suddenly remember something, for his smile fades and he looks at me sternly:

“Ai Qing, do not talk to anyone else besides Rajiva about your true identity, and do not tell anyone their future. Also, do not use your abilities from the future unless you absolutely have to.”

He gazes out at the windows. His mind seems to be full of erratic thoughts. He looks like there is a cloud hovering over him, making his brows furrowed.

“[I am] afraid that, you being able to foresee the future, in these turbulent times, would be of more interest to those who ambitious and ruthless in character than your identity as a celestial being…”

My heart shudders. The way he speaks resembles that of my ‘boss’1. But ‘boss’ said this to me because he did not want me to alter history, whereas he [Rajiva] is only worried about my safety. Before, I did not care about this because I thought of myself as a tourist and that if anything major happens, I can just go back to the modern times. But if you really want to survive in this miserable era of chaos, the instant you are inattentive, it can possibly result in ‘misfortune from the mouth’2. Now that I am no longer by myself, I cannot run away—I cannot hurt him.

1 ‘Boss’ here refers to the nickname Ai Qing has for her history professor, who is the advisor to the time travel project.

2 祸从口出 huòcóngkǒuchū – a chengyu (Chinese four-character idioms—I’ve been referring to them as simply ‘Chinese idiom’ in my previous T/N but that was too broad of a term. 成語 or chéngyǔ, lit. ‘[already] formed words’, is the correct term). This chengyu, as you can probably tell from the words, means that a loose tongue can cause trouble.

I give him a [modern] military salute and solemnly swear:

“Worry not, I will only focus on the role of being your wife; absolutely only have ‘eye looking at nose, nose looking at heart;’1 ‘cautious in words, careful in behaviour;’2 low-profile in conduct; and never disclosing my secrets.”

1 眼观鼻,鼻观心 (yǎn guān bí, bí guān xīn) – the above is a literal translation; this is a Chinese expression that has two meanings (per baike baidu): 1) to indicate bowing one’s head out of shyness/embarrassment, and 2) having a focused mind, heart not distracted. The second meaning applies in this context.

2 谨言慎行 (dīdiào zuòrén) – a chengyu that came from《礼记 · 缁衣》or Lǐjì – Zī Yī (Book of Rites – “Black Robes”), which is a classical text in Confucian canon.

He laughs, dazzling the room with his elegant and handsome face. It has been a long while since I have seen him laugh so freely that for a moment, illicit [desires] arise and like a smitten fool, I stare at him open-mouthed.

He brushes my nose and asks softly, “Only a wife?”

“Huh?” I swallow my saliva* and stare at him, puzzled.

[T/N: Basically, she was drooling over his handsomeness after seeing him laugh earlier]

A familiar blush takes over his face. He embraces me from behind, head resting on my shoulder, slender palms gently covering my flat stomach.

“Could it be that…” he pauses, breath a bit heavy, voice a tiny whisper right into my ear, “you do not want to be a mother?”

I freeze. Mother? Child? Children of him and me?

I turn around and see that his clean, relaxed face is blushing, yet he is also looking at me with a fixed gaze, a shy and expectant smile on his lips.

“You…” Somewhat unsure, I whisper and ask, “You want to have children?”

“Rajiva has never dared to think that there will be a child sharing his blood in the world.” His face has been blushing this whole while, but his eyes are firm, “After living together with you, however, [I] really want to have a child. If possible, give birth to a girl who looks like you. Rajiva will definitely love the child with all of his heart.”

My nose stings: “Are you not afraid of denouncement from people?”

“Breaking precepts, taking a wife, which one to denounce? You know [me], the comments by this generation or later generations, Rajiva does not care at all.” His face looks calm, but there is still a note of melancholy when he pauses in thought, “I just want to have a child of ours, [so that] in the future, if you have to go back, allow me to keep the child-”

“I will not leave!” I cover his mouth and speak fiercely, “Do not forget, we have tied our hems to promise a hundred years.* You want to get rid of me? In your dreams!”

* [See Ch.55, specifically my T/N for the chapter’s title]

His eyes burn in response, brows finally loosening, and then a light peck is placed on the palm of my hand that is covering his mouth. Something numb travels down my spine, my whole body shudders slightly. He picks me up—he likes to carry me to the bed these days. Ear and temple rubbing against each other1, fluttering and lingering, yet at the moment when the climax is reached, he suddenly withdraws. He has never acted like this before, so I cannot help but ask, breathless: “What’s the matter?”

1 耳鬓厮磨 (ěr bìn sī mó) – lit. ‘ear [and] hair on temple rubbing against [each other]’, this is a chengyu that is also a euphemism for intimate relations [or per MDBG: “a very close relationship”, snort], which originated from 紅樓夢 (Hónglóumèng) or Dream of the Red Chamber, one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels. [It does not surprise me that a euphemistic idiom was derived from this novel. But also, fun fact: ‘Redology’ is a term used to describe the field of study exclusively devoted to this novel!]

He is still breathing heavily, takes a moment to rest, then brushes aside my sweaty hair and softly says:

“At present, it is not yet the time to be carrying a child. We will be departing in the third month of next year, and it would take half a year to arrive at Guzang.* There will be many bumps on the road, if you are pregnant, how will you be able to endure?” He reaches out and pulls me into his arms, and then kisses me on the forehead, “Once we arrive at Guzang and everything settles down, our household can have one more addition.”

* Guzang (presently part of Wenwu, Gansu) was the capital of Former Liang (320–376 CE), Later Liang (386-403 CE) – the state established by Lu Guang, and Northern Liang (397-439) – established by Duan Ye.

Map of China during the Sixteen Kingdoms Period as of 391 AD

I bury my head in his arms and listen to his powerful heartbeat. I smile shyly but deep in my heart, I am full of worries. We have never tried to prevent pregnancy, but what he said today has reminded me. Half a year on the road, over a long distance and using transportation in the ancient times, will definitely not be as comfortable as travelling in the modern times. Under such circumstances, I really should not get pregnant before we reach Guzang. But what I worry about the most is not this but: Can I even get pregnant? This body has been in and out of the time-travel machine several times. I do not know whether irradiation has damaged my fertility or not. And even if I can get pregnant, will I be able to give birth smoothly? I am not afraid of the primitive delivery techniques of ancient times, but I cannot sustain any injuries.* Would giving birth be counted as an injury?

* [T/N: As a refresher – during her last time travel, Ai Qing has learned that irradiation has caused her body to heal at a much slower rate, which was why the wound on her arm never healed properly, almost resulting in necrosis, so she had to return to her era to get surgery. See Ch. 34.]

I have tried to tell him many times, but looking at the way the corners of his mouth are curving and how he eager he is about the future, I end up holding back. If he learns of the true price I paid for my journey, how much worry and guilt would it bring to him? Our happiness is so hard-won—I cannot destroy it.

I glance outside. My backpack is currently lying in some storage room, with my time-travelling watch and anti-radiation jacket stored inside. There were many times where I wanted to throw away this source of radiation,* but I kept thinking about boss’ words. Hesitant and indecisive, in the end, I was unable to sever the ties with the 21st century. I could only store the bag far away from my sight and hope that I would never have to use them again.

[T/N: The items she brought from her era, like her, have also been contaminated with radiation during the time-jump. This was why she never brought along any perishables.]

“What are you thinking about, looking so silly?”

He is lying on his side, looking at me, his hand playing with my hair, eyes overflowing with affection.

“There is another way to prevent carriage.”

I regain my spirits and explain to him the concept of ovulation and safe period [in menstruation cycle]. He listens carefully and asks me in detail about my modern physiology knowledge, frequently exclaiming in admiration of the wisdom gained after a thousand years. I cannot help laughing inside. He really has come to accept that his wife is a person from the future.

An illustration of Wu Song at the Long Corridor in the Summer Palace, Beijing

The happy little days momentarily make us forget about our worries. My cooking skills have improved a lot, so he often brings the lunchboxes I made for him to the temple. After learning how to cook in ancient times, I also begin to learn how to wash clothes the ancient way. No washing machine, no detergent, no fabric softener, just balls of [Chinese] honey locust1, a washing board, and a wooden staff. The first time I followed Elder Sister Adoly to wash clothes at the Tongchang River, because I did not know how to use the staff, I almost broke into the posture of Wu Song beating a tiger2, causing laughter from the other women by the river.

1 Scientific name: Gleditsia sinensis, known in Chinese as 皂角 (zàojiǎo) [not to be confused with the North American-native plant], the seeds of the plant were turned into powder and kneaded into a ball, which produces bubbles when used so was highly effective for washing clothes. ‘Soap’ in Chinese is 肥皂 (féizào), which as you can see, derives from the name of the plant.

2 Wu Song is a character in Water Margin, one of the Four Great Classical Novels in Chinese literature, who often fights with a staff as his weapon. There is a story about Wu Song defeating a tiger in the novel.

Choy Sum

On my way home after washing clothes, the people I meet on the streets all avoid me. I tell myself that it is okay, that I do not need to mind what others think of me. I stand tall, hold my head high, and keep walking. But all of sudden, a woman steps forward to stop my tracks, scaring me. She gives me a handful of choy sum* and says hesitatingly:

* The text says 菜心 (càixīn), which is a transliteration of the Cantonese name.

“Princess, this was just picked. The master made a prayer of blessings to treat my child, and it was the master’s Bodhisattva-heart that saved him. My family is poor, we got nothing else, so I hope Princess will not mind. May Princess and the master be blessed with peace and luck!”

In a daze, I take the choy sum, which still has drops of water dripping from its young green leaves. This is the first time I have received blessings from a stranger. Aside from thanking her, I am not able to say anything else. When I arrive home, I keep staring at the choy sum until Rajiva returns. I excitedly tell him the origin of the vegetable. He merely smiles, lost in thought.

The next day, he unexpectedly returns home earlier than usual. I am learning how to make naan in the kitchen. He asks me to wash off the flour on my hands and face and go change, but does not say what for. After I have finished changing per his inexplicable request, he takes my hand and walks out onto the streets.

My heart is shocked. I have never walked with him so openly, let alone while holding hands! I want to withdraw my hand, but he only holds it tighter. He smiles at me, a smile like a spring breeze, filling my heart with a breath of warmth. I hold myself tall and smile back at him. Together, we walk on the streets of Subashi City.

Anyone who sees us is unable to hide their surprise. Rajiva greets people as always, humble and respectful, but his bearing is exceptional. Having been the abbot of the Cakuri Temple for so many years, he has come to know all of the residents of Subashi. He brings me to every door, chatting with people as if we are an ordinary couple on an evening stroll after dinner. The initial awkwardness eventually eases into acceptance as more and more people begin to talk to us, some calling me “Princess”. There are also many monks on the streets. They look at me in surprise when they pass by, but still clasp their hands to greet Rajiva. He returns their greeting as usual, but also insists on them calling me ‘master’s wife’1. It is dark by the time we get back. My hands and his are full of things—all kinds of vegetables, fruits, and daily necessities. They were given to us by the people, and it was useless to even try to refuse.

1 师母 (shīmǔ): a respectful term for your 师父 or shīfu (master/teacher)’s wife.

From then on, every time I leave the house, I no longer receive looks of suspicion. Every day, there is always someone who comes to visit me, gives me things, and talks to me. Even though I am not used to being an object of curiosity, being accepted by the public makes me quite happy.

Rajiva is reading by the oil lamp, while I sit beside with my basket of threads and needle. I place a sheet of sketching paper on the ground, tell him to take off his shoes and step on it, then I use a pencil to sketch the outline of his feet. The past few days, Elder Sister Adoly has been teaching me how to make cloth shoes and how to fill the soles. My sketching paper has found a new use. In the sewing basket is a garment of his that has a hole on the elbow, which he refused to get rid of. After tracing the outline for the shoes, I sit quietly beside him, cut a piece of cloth of the same colour, and patch up his shirt.

“Ss!”

Sure enough, he drops his book and checks my finger. Then, as I expected, he puts my finger in his mouth and sucks. Haha, I have looked forward to this warm scene!

“Why do you need to do this work?” He raises his eyes and upon seeing me giggling, looks a little angry, “Why not let Elder Sister do it?”

I raise my eyebrows at him, full of mischief, not wanting to explain to him that I wanted to experience this. There is a scene that often appears in historical dramas: the scholar husband is reading; his gentle wife is sitting beside, doing needlework. Then the wife pricks her finger with the needle, and the husband sucks on her finger, full of heartache. The men and women of the 21st century are always busy. Even if a married couple is at home at the same time, one is watching soccer and the other is surfing the Internet. It is hard to find the warm scene of “trimming candle’s wick together by the west window”.*

* This is a reference to a line in the poem《夜雨寄北》by Li Shangyin:

《夜雨寄北》

君問歸期未有期

巴山夜雨漲秋池

何當共剪西窗燭

卻說巴山夜雨時

“Written during the rain one night and sent back north”

You asked when I was coming back

no date fixed yet;

in Ba’s hills the rain by night

spills over autumn ponds.

When will we trim candle’s wick

together beside west window

and speak back about this moment

of night rain in hills of Ba?

– Stephen Owen, Anthology of Chinese Literature (Beginnings to 1911), p. 515

Such a state of mind, I do not know how to explain to him, so I can only flash him my silly grin and try to change the topic:

“What book are you reading?”

My casual question somehow makes him blush. Curious, I pick up his book. Rajiva studies a wide range of areas, reads almost every kind of book, and is also a fast reader with a superb memory. What he was reading is a medical text in Han. I know he sometimes studies medicine and occasionally treats people, but why the blush? Suspicious, I open to the page he was reading. The word ‘gui shui’* jumps into my eyes. My cheeks redden.

* 癸水 (guǐ shuǐ): ancient Chinese term for menstruation. 癸 = the 10th Heavenly Stem (Heavenly Stems were names of the days of week), and 水 = water. The ten Heavenly Stems also correspond to 五行 ( wǔxíng) the Five Elements—each element contains two Heavenly Stems, further broken down into yin and yang. 癸 corresponds to the yin of the Water element.

When we were under the house arrest, he once saw me leaning forward, clutching my abdomen in pain. Frightened, he quickly checked my pulse for a diagnosis. I had blushed and explained to him about menstrual cramps, and how they would make me suffer for hours on the first day [of my period]. He was so flustered that he did not know what to do with his hands and kept asking me, “Does it still hurt?”

The second time he witnessed it was after we got married. Having gained some experience, he was extremely gentle with me during those days and tried to help by rubbing my stomach. I did not expect him to now read a book on how to treat menstrual cramps. A current of warmth travels through me. Looking at his flushing face, I cannot help but laugh.

“You will feel pain in three days.” Seeing me laugh, he looks a bit annoyed. “Tomorrow, I will ask Kaodura to get medicine. You must try to drink it, for it will help.”

I freeze for moment.

“How do you know the time [when it will happen]?”

“I am your husband, naturally I ought to know,” he gently knocks on my forehead, his face still red, “Only you, scatterbrained* lady, would not even remember this.”

*傻头傻脑 (shǎtóu shǎnǎo), a chengyu that originated from Hongloumeng. 傻 = foolish / silly, 头 = head, and 脑 = brain.

I stick out my tongue. To be honest, I never keep track of my menstruation cycle. Because a menstruation cycle is 28 days,* which is different from the number of days in the Gregorian calendar month, so I always get confused. Whenever I feel like my period is approaching, I would bring along sanitary pads. In preparation for this time jump, I had stuffed two years’ worth in my backpack, taking up quite a big amount of space.

* [T/N: Just want to correct that it is 28 days on average, but this is not universal for all people. To be more accurate, the range is 21-31 days.]

I wrap my arms around his waist and lean against his shoulder, acting spoiled1:

“Your memory is better than mine, so you remember it for me!”

1 撒娇 (sājiāo) [T/N: According to Chinese people, this is one of the most difficult words to translate as there’s no single English word that can encompass every aspect of it. It was once a gendered term/act (women’s) but is now gender-neutral. Depending on context, it can be translated as: cajole / pout / sulk / wheedle / coquettish / flirt / etc. One can use it as a child, as an adult, and the receiving end can be a family member, a friend, or a lover. It is acting cute with a dash of brattiness, but short of being annoying. To be able to sajiao at someone indicates an easy familiarity and that you feel confident of their love for you. There is an equivalent word in Vietnamese, which is “làm nũng” or “nũng nịu”, so I can empathize with the Chinese on the difficulty of translating this word.]

“You…”

I tighten my arms around his waist and bury my head into his chest, breathing in his scent: “One who is loved is qualified to be lazy.”

He laughs and pulls me onto his lap. I hook my arms around his neck, rest my head against his shoulder, and quietly read the book with him. He is my comfortable stool, forever a stool.

An old song comes to mind: “[I] once asked over and over, secretly in the dark / Only to know that a simple and leisurely life is the truth.”1 No matter how dazzling and beautiful a love is, it will eventually dull. But a dull life where one can moisten each other with spittle2, sharing warmth with him bit by bit3, already makes me feel as sweet as syrup4.

1 Lyrics from the song《再回首》”Looking Back” by Taiwanese singer Su Rui, released in 1988. [See T/N at the end of chapter for further notes on the lyrics as it contains a few chengyu.]

2 相濡以沫 (xiāngrúyǐmò), a chengyu: describes how two fishes would pass the water in their mouths between each other to survive; it means aiding each other in difficult times with whatever meagre strength you have.

3 点点滴滴 (diǎndiǎndīdī), a chengyu: lit. dot, dot, drip, drip.

4 甘之如饴 (gānzhīrúyí), a chengyu: means to willingly and gladly endure hardships together.

In this way, we enter the winter of 384 CE without any major winds and waves. His work turns fruitful: Most all the monks who fled before have returned, and everything in the temple has returned to normal. The suffering people endured during the war has made them more devout and faithful towards Buddha, which in turn makes him busy but happily so. And I have also mastered more survival skills of the ancient times—can cook, wash, sew, make shoes, and pickle. Every day, I follow Elder Sister Adoly to the market to buy food, and also foster a relationship with the neighbourhood ladies. Gradually, I begin to assimilate into the life of 1,650 years ago.

Of course, sooner or later, Lu Guang is going to call us to mind. That is why, after Kucha got its first snowfall, I see Di soldiers standing outside the gates. I smile bitterly. So the time has come early.

____________________________________________________________________________

Translator’s Notes:

RE: Chapter’s Title

Original text: 平平淡淡才是真

Pinyin: Píngpíngdàndàn cái shì zhēn

This chapter’s title refers to a popular Chinese saying but before we go there, we must first discuss the chengyu (yes, another chengyu) referenced within: 平平淡淡

平平 = average / plain

淡淡 = faint / dim / dull / insipid / unenthusiastic / indifferent

This is a chengyu that originates from 圍城 or Fortress Besieged (1947) by Qian Zhongshu, a satirical novel about middle-class Chinese society in the late 1930s (Source: Wiki). The chengyu is used to describe something that is average or below average, ordinary in quality, almost dull. Context of the phrase: The main character in Fortress Besieged was musing about his tepid feelings towards his fiancée:

“…假如再大十几岁,到了回光返照的年龄,也许又会爱得如傻如狂了,老头子恋爱听说像老房子着了火,烧起来没有救的。像现在平平淡淡,情感在心上不成为负担,这也是顶好的,至少是顶舒服的。快快行了结婚手续完事。” [Chapter 62 of Chinese text]

English: “If he were ten or fifteen years older and reached the moment of “twilight brightness,” maybe he could fall foolishly and madly in love. An old man’s love was said to be like an old house set ablaze. Once it started burning, there was no saving it. In the dull state he was in now, his emotions did not constitute a burden on his mind, which was just as well. At least it was quite comfortable. Better to get the marriage procedures over with as quickly as possible.” (Kelly, Jeanne, and Nathan K. Mao, translators. “Chapter 8.” Fortress Besieged, by Zhongshu Qian, New Directions, 2004, p. 293.) [In case you were wondering, yes, I got a copy from the library.]

Ironically, the chengyu is now part of a popular Chinese saying that claims such “dull state” is actually “truth” (真= ‘really / truly / true’), and that it is an ideal kind of life. This Chinese saying is our chapter’s title. From what I learned (ahem, through baike baidu and zhidao baidu; think Wiki and Quora), the meaning of the saying is not so much about living a simple life avoiding fame and fortune, but more about having a serene (or indifferent, depending on interpretation) heart as you go about life, about bearing the ups and downs in life calmly. With this second reference in mind, I decided to translate the chengyu as “simplicity”.

An alternate translation of this Chinese phrase (and in turn, this chapter’s title) that would capture the meaning better is “Simplicity makes life” (Huang Weijia and Sun Jiahui’s translation). I admit I like this translation better as there is a certain elegance to it, but I have already taken liberties with translating the chengyu so I decided to stick with a more literal translation for the rest of the phrase.